Artificial Intelligence is making breakthrough advancements in image recognition, natural language processing, robotics, and machine learning in general. The company DeepMind, a leader in AI research, has created AlphaZero in 2018, an AI program that has reached superhuman performance in many games including the game of Go, and more recently in 2020, AlphaFold that solved a protein folding problem that has preoccupied researchers for 50 years. For Stanford Professor Andrew Ng, AI is the new electricity.

A more useful comparison would be the advent of the personal computer, in particular, the IBM PC in 1981, and its first killer application, the spreadsheet software Lotus 123. IBM didn’t introduce the first computer. Home computers were already available for hobbyists since 1977 from companies such as Commodore, Tandy, and Apple. The Apple II with Visicalc was especially already very popular but the IBM PC was the first affordable personal computer enthusiastically adopted by the business community.

Figure 1. IBM PC

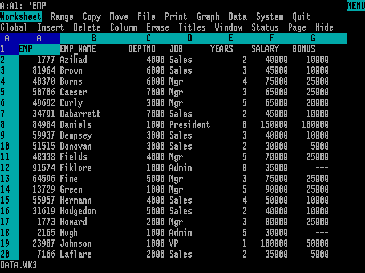

Figure 2. Lotus 123

The novel spreadsheet software allowed flexible free-form calculations, the automation of calculations, the use of custom functions, graphics, references, and data management. Excel, the dominant spreadsheet software is still in use more than thirty years after its first introduction (with more functionalities). Before the spreadsheets, people used calculators and reported results on paper. More intensive calculations were done with mainframe computers in a language such as FORTRAN and results were printed on paper.

Today, AI is the new PC. Not adopting AI is like forgoing the PC in 1981. The impact is already very profound among the native digital companies and should be as significant for the rest of the companies.

Today, business leaders need to think about an AI strategy as they have to think about their information technology strategy. Like the PC and the spreadsheet, they should expect all their employees to become at some point users of AI at work. As the home computer, AI is already present at home with personal assistants such as Amazon Alexa, on phones with Apple Siri, and the internet with Google. All these AI applications are now possible thanks to increasing computer power, the development of the cloud, the availability of big data, and the new machine deep learning paradigm.

The AI Strategy Handbook was written to help you adopt AI in your business strategy so that it creates a long-term sustainable competitive advantage for your customers, your company, your employees, and your investors.